It’s hard to imagine that perfection would be possible in 2011.

In this very uncinematic era ruined by technology.

But it takes a genius to produce art from tech.

And it takes an artist to produce art.

Martin Scorsese was well up to the challenge.

As the weirdo I am, The King of Comedy has always been my favorite of his films.

Rupert Pupkin spoke to me in a way that perhaps only the totality of Dr. Strangelove ever similarly did.

But Mr. Scorsese had the brass to undertake a project which should have been doomed if only by its trappings.

Films have tried and generally failed at relative tasks.

City of Ember, for example.

But Scorsese was not deterred.

Not least because he had the magical trump card: Méliès.

Which is to say, he had the story to end all stories (as far as cinema is concerned).

The big daddy. The big papa.

Papa Georges.

But first things first…

We must give credit to Asa Butterfield (who looks like a cross between Barron Trump and Win Butler in this film).

Butterfield is no Mechanical Turk.

Nay, far from it.

But automata (or at least one particular automaton) play a large role in Hugo.

And why “Hugo”?

Kid living “underground”? Victor? Les Misérables?

Yes, I think so.

And it’s a nice touch by the auteur (in the strictest sense) Brian Selznick.

[Yes, grandson of David O.]

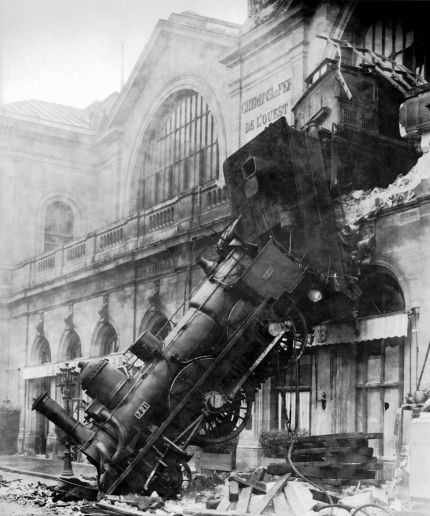

We’re at the Gare Montparnasse.

Torn down in 1969.

Site of this famous 1895 derailment.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, I’m up to 1,261.

But we press on…

Because Méliès was about dreams.

And Hugo is about dreams.

les rêves

And Scorsese has been “tapped in” to this magic at least since he portrayed Vincent van Gogh in Akira Kurosawa’s Dreams (Kurosawa-san’s best film).

I must admit…I was a bit confused for awhile.

Something told me Scorsese had transformed himself into Méliès.

It was only later that it all made sense.

Ben Kingsley.

I mean, Scorsese is a great actor (Van Gogh, etc.), but he’s not THAT great!

But I’m jumping ahead…

Sacha Baron Cohen is very good in a somewhat-serious, villain role here.

I fully expected the immensely-talented Cohen to “ham it up” at some point, but he instead gives a very fine, restrained performance which fits like clockwork (sorry) into the viscera of this exquisite film.

But let’s revisit Sir Kingsley.

What a performance!

The loss of a career (Méliès).

The loss of a previous life.

The fragility of celluloid.

All to end up running a pathetic souvenir shop.

Toys.

Very clever, but still…

Such a fall from grace.

Into such obscurity.

I can only compare it to the trajectory of Emmett Miller (which was so artfully documented by my favorite author of all time [Nick Tosches] in my favorite BOOK of all time [Where Dead Voices Gather]).

The speed at which technology moves has the potential to reduce the most eminent personage to mere footnote at breakneck speed.

It was so even a hundred years ago.

And the process has now exponentially accelerated.

But we are coming to understand the trivialization of the recent past.

We are holding tighter to our precious films and recordings.

Because we know that some are lost forever.

Will this vigilance continue uninterrupted?

I doubt it.

But for now we know.

Some of us.

That today’s masterpieces might slip through the cracks into complete nonexistence.

Consider Kurt Schwitters.

The Merzbau.

Bombed by the Allies in 1943.

Es ist nicht mehr.

Into thin air.

But such also is the nature of magic.

Poof!

Skeletons later evoked by Jean Renoir in La Règle du jeu.

Scorsese is a film historian making movies.

And it is a wonderful thing to see.

And hear.

Saint-Saëns’s Danse macabre more than once.

As on a player piano.

With ghost hands.

And the gears of the automaton.

Like the mystery of Conlon Nancarrow’s impossible fugues.

I’m betting Morten Tyldum lifted more than the spirit of gears meshing in Hugo to evoke the majesty of Alan Turing’s bombe in The Imitation Game.

But every film needs a secret weapon (much like Hitchcock relied on the MacGuffin).

And Scorsese’s ace in the hole for Hugo is the Satie-rik, placid visage of Chloë Grace Moretz.

Statuesque as water.

A grin.

A dollar word.

The beret.

And the ubiquitous waltzes as seen through keyholes and the Figure 5 in Gold.

Hugo is the outsider.

Scruffy ruffian.

Meek. Stealing only enough to survive. And invent.

But always on the outside looking in.

Below the window (like in Cinema Paradiso).

Ms. Moretz’ world is lit with gas lamps.

And you can almost smell the warm croissants.

[Funny that a film set in Paris should require subtitles FOR PARISIANS]

Assuming you don’t speak English.

Tables are turned.

But Paris draws the cineastes like bees to a hive.

THE hive.

Historically.

And that is just what this is.

History come alive.

But another word about Ms. Moretz.

As I am so wont to say in such situations, she’s not just a pretty face.

Though they are faint glimmers, I see an acting potential (mostly realized) which I haven’t seen in a very long time.

The key is in small gestures.

But really, the key is having Scorsese behind the camera.

It’s symbiotic.

Martin needed Chloë for this picture.

And vice versa.

We get a movie within a movie.

And (believe it or not) even a dream within a dream.

Poe is ringing his bell!

Or bells.

“Lost dream” says Wikipedia.

Yes.

It is as bitter a music as ever rained into Harry Partch’s boot heels.

To have one’s life work melted down for shoes.

Rendered.

To click the stone of Gare Montparnasse.

In an ever-more-sad procession.

Méliès becomes the vieux saltimbanque of which Baudelaire wrote.

Such is life.

We never expected to end up HERE.

Astounding!

-PD